In a new book, Yale historian Michael Brenes argues that engaging in great-power competition with China ultimately weakens the United States both at home and abroad.

The rise of China as a global power has cast a shadow over U.S. foreign policy. For nearly a decade, elected leaders from both major political parties have described China as a sinister threat to America’s national interests and democracy worldwide.

As a result, the U.S. government has committed to a full-throated rivalry with China reminiscent of its Cold War with the Soviet Union.

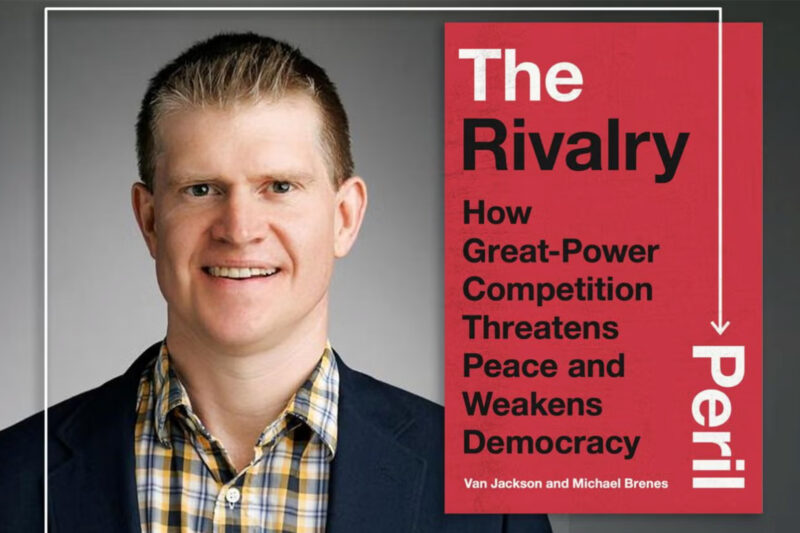

Michael Brenes, co-director of the Brady-Johnson Program in Grand Strategy and lecturer in history at the Jackson School of Global Affairs, argues that engaging in a “great-power competition” with China is misguided and will ultimately harm U.S. interests domestically and abroad.

His new book, “The Rivalry Peril: How Great-Power Competition Threatens Peace and Weakens Democracy,” makes the case for taking a less aggressive approach to China. This, he argues, would ease tensions between the two powers and achieve constructive diplomacy, enhancing their ability to effectively address climate change and other pressing global challenges.

Brenes and co-author Van Jackson, an international affairs scholar at Victoria University of Wellington, argue that applying an antiquated Cold War dynamic to the United States’ relationship with China overlooks the bloodshed and instability that the rivalry between the U.S. and Soviet Union wrought globally during the 20th century.

In a recent conversation, Brenes discussed the risks of taking a confrontational approach with China and the benefits of adopting a foreign policy that acknowledges the genuine threats it poses while seeking opportunities for cooperation. The interview has been edited and condensed.

What are proponents of great-power rivalry with China getting wrong?

Brenes: Great-power competition with China assumes that the United States is engaged in a new Cold War with China. The rise of China as a great power, combined with Chinese President Xi Jinping’s assertive and nationalistic view of his country’s role in the world, has made U.S. policymakers see a return to the dynamics that existed during the Cold War with the Soviet Union. That is, they see two superpowers, the United States and China, locked in a struggle over the future of the planet.

In their view, the United States can, as it did during the Cold War, rely upon its military strength, economic might, political influence, and its image as a democratic power to constrain China from exerting greater influence over the world while maximizing its own. They see the stakes as existential.

But I think great-power competition is leading us down a dark path. In the book, we argue that proponents of great-power rivalry with China draw on a selective history of the Cold War. They imagine the Cold War as a zero-sum struggle with the Soviet Union that ended in an unequivocal victory for the United States and its allies in 1991. That ignores the large-scale violence inherent in the Cold War and the instability it produced. We argue that this oversanguine view of the Cold War underestimates the costs and risks of geopolitical rivalry to economic prosperity, the quality of democracy at home and abroad, and global stability.

What does an accurate reading of Cold War history suggest about the dangers of great-power competition?

Brenes: The Cold War led to the fall of communism, but it also was a period in which the United States and the Soviet Union waged bloody proxy wars throughout the world. The United States engaged in clandestine counterinsurgent activities that led to the overthrow of democratically elected regimes in countries like Chile and Guatemala. We destabilized these countries in ways that came back to haunt us.

Iran is a clear example of this. In 1953, the CIA backed a coup that overthrew Mohammad Mosaddegh, Iran’s democratically elected prime minister, and led to the Shah taking power. Backlash to the Shah’s rule culminated in 1979 with the Iranian Revolution and the Ayatollah seizing power. The United States and Iran have been in tension ever since.

Trying to prevent communism from taking hold in Vietnam led to a nearly 30-year war that killed millions of Vietnamese and more than 58,000 Americans. In the end, communist North Vietnam took control of the country. The point is that the long process of defeating communism during the Cold War unleashed a lot of instability that continues to shape the world today.

This history is instructive when thinking about the future of great-power competition with China. The U.S. might think its actions toward China reflect its national interests now, but they may backfire in unexpected ways down the road.

How is the rivalry with China weakening the United States?

Brenes: If great-power competition with China is supposed to rejuvenate our democracy and drive our economy, we haven’t seen it yet. And I don’t think we’re more likely to see it in the future.

One major cost is to democracy itself. The anti-China rhetoric utilized by Republicans and Democrats has stoked anti-Chinese sentiments that exacerbate nativism and xenophobia, which erodes the foundation of a pluralistic, multiracial democracy like the United States.

We’ve seen an increase in anti-Chinese xenophobia, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. We’ve also seen then the rise of hate crimes against Chinese and other Asian people in the United States as a result. Moreover, bad actors exploit the rivalry with China to spread baseless conspiracy theories about China’s involvement in our politics. This harms national cohesion, pulling us apart instead of bringing us together.

In economic terms, there are arguments that great-power competition with China creates jobs and drives innovation as we seek to maintain technological and military dominance over China. This is true to a certain extent, but also very limited. Competition with China only creates jobs for a select few Americans. It’s not a mass-employment program by any stretch. Again, the Cold War brought prosperity to some, but it also heightened racial and economic inequality.

You mentioned that great-power rivalry harms national cohesion. How so?

Brenes: Another flawed reading of history is the idea that the Cold War united Americans, regardless of political party, in an existential contest against communism. That ignores the rise of McCarthyism and the Red Scare — the creation of federal loyalty programs and suspicions that communists pervaded all levels of government and had infiltrated our schools. Advocates for civil and women’s rights were denounced as communists.

We see hints of this sort of demonization today. If a lawmaker argues against spending more on the military budget, or cooperating with China on certain issues, they will be accused of being pro-China or anti-American. Rivalry with China is used to delegitimize counterarguments and squash dissent. It stymies free speech and the free exchange of ideas as they relate to the country’s future, not just in terms of U.S.-China relations but also regarding issues like climate change, economic inequality, and global democracy.

What would be a more productive way to engage with China?

Brenes: China certainly poses threats to the United States and the world. It violates the human rights of its Uyghur population [a Turkic-speaking ethnic group located primarily in the northwestern region of Xinjiang]. It commits intellectual property theft and has been responsible for cyberattacks and unfair trade practices, among other bad behavior. But I don’t think the totality of these various threats makes China an existential threat to the United States and to freedom around the world.

A better approach to China would take stock of the challenges it poses to the world but also consider that there are some crucial issues where the United States needs to work with China. The most important of these is climate change, where China is currently outpacing the United States in terms of the production of green technology. The Biden Administration characterized this as a threat to our national interests, but that is the wrong way to think about it given that climate change affects the entire world, particularly its poorest nations. A more cooperative stance is necessary on climate change and other issues that transcend borders, such as nuclear proliferation, drug trafficking, and sovereign debt crises. These issues demand that the international community come together and think creatively about how to solve them.

Much of the world, particularly the Global South, is rejecting great-power competition as a framework for organizing world affairs. Many of these nations look to China as a benefactor of some kind through its Belt and Road Initiative and other programs, and they are reluctant or unwilling to repudiate China’s influence. We would be in a much better position globally, and could attract the interest of the Global South, if we rejected great-power competition and instead thought more carefully about what we can do to help poorer nations improve their condition, and not simply frame every issue as part of a competition with China that has no end in sight.