In his new book, Professor Ian Shapiro defends the Enlightenment principles of science and reasoned thinking against philosophical assaults from the right and left.

Ian Shapiro admires Tom Paine, the English-born American revolutionary whose 1776 pamphlet “Common Sense” galvanized support for independence from Great Britain, whose “American Crisis” letters sustained the American forces through the darkest days of the Revolutionary War, and whose “Rights of Man” remains an inspiring manifesto for the downtrodden.

“At some of the darkest times in both American and British history, Paine put his shoulder to the wheel and never gave up on the possibility of making Enlightenment thinking useful in politics,” said Shapiro, Sterling Professor of Political Science and Global Affairs in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences and at the Yale Jackson School of Global Affairs. “His life and writings remind us that reasoned thinking and compelling arguments can be efficacious in politics even in eras like ours, when the path forward is murky at best.”

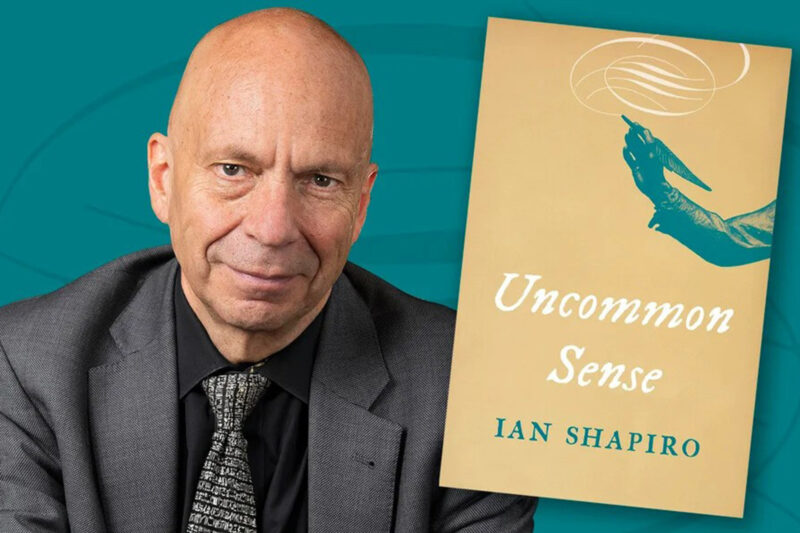

Shapiro’s latest book, “Uncommon Sense” (Yale University Press) — the title is an homage to Paine — defends the core Enlightenment commitments to reason and science, arguing that they offer the best available resources to resist political domination and improve the human condition. In recent decades, these commitments have come under sustained assault from both the post-modern left and the authoritarian right.

Shapiro maintains that these attacks are dangerously misguided.

In a recent conversation, Shapiro discussed how efforts to abandon the Enlightenment project have contributed to the bleak state of contemporary politics. He argues that embracing the pursuit of knowledge through the methods of reason and science is vital to restoring confidence in democratic institutions and sustaining them into the future.

The book’s opening section examines philosophical critiques of the Enlightenment project from thinkers who represent both the ideological right and the left. What do those critiques get wrong?

Ian Shapiro: The chapters in part one support the contention that, while critics who say the Enlightenment was unrealistically ambitious were persuasive in some ways, they overreached. The critics are convincing that the Enlightenment’s champions were misguided to believe that we will ever identify universal principles of justice and neutral outcomes in politics. But I argue that to junk the whole Enlightenment project because of this overreaching is to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

The commitments to reason and science survive the Enlightenment’s failures. If we abandon them, not only do we land in a philosophically unappealing place, we supply intellectual ballast to the people who talk about fake news and alternative facts and politicians who declare their own reality. It’s a strategy that underwrites today’s baleful politics — however unwittingly.

The book also features chapters based on papers you’ve written about democracy and the philosophical underpinnings of contemporary politics. How do critiques of the Enlightenment project influence the rise of populism, the decline of effective political parties, and other features of our current political situation?

Shapiro: In those chapters, I show how rejecting Enlightenment commitments has played out, producing ill-considered efforts at political reform. At best, they are irrelevant and often they make things worse by weakening political parties and undermining democratic institutions more broadly. This makes effective governance harder, which, in turn, compounds voter alienation and helps legitimate authoritarians who attack democratic politics as hopelessly muddled and inept.

In this world, it’s hard not to be reminded of the 1930s, another era in which weak and fragmented parties and parliaments became ever-more dysfunctional, making it easier for fascists and other vanguardists to seize power.

You also focus on sources of hope. What’s the bright side?

Shapiro: The chapters comprising parts one and two present a pretty gloomy picture, so I thought it appropriate to share some reasons to be hopeful that we can improve things. The penultimate chapter explores the ways in which Isiah Berlin’s pessimistic assessment of the prospects for human freedom during the Cold War were exaggerated, even if he was right to remind us that insecure people can easily be mobilized by authoritarian figures. The answer is to pursue policies that address the sources of their insecurity.

The last chapter is adapted from a paper I originally wrote with [political scientist] James Read about the transition to democracy in South Africa. When I left South Africa in 1972, I and everyone I knew thought it obvious that apartheid was doomed, but nobody believed that there was going to be a peaceful transition to a democratic order. We thought, instead, that there would be a draconian authoritarian crackdown, a civil war, or both. Those things didn’t happen. It’s a good illustration that life sometimes has more imagination than we do.

Consider people who came of age in the West during the late 1940s. They had grown up during the two most devastating wars in human history, the collapse of democracies, and the rise of communism and fascism. If anyone had said to them in 1945 that the Western world was about to embark on six historically unprecedented decades of stable democracy, economic growth, and social improvement, they would have been laughed out of the room. In 1985, the great majority of South Africans would have been just as incredulous of anyone who had predicted what in fact happened: a peaceful transition to a democratic order.

Even when things look exceedingly bleak, there can be reasons to be hopeful that reasoned argument can prevail in politics — opening paths to a better future. One of Paine’s most enduring lessons is that no matter how bad things are, it never makes sense to abandon hope in the possibility of a better future or to give up working toward it.

Disdain for expertise has affected discussions about responses to the pandemic, climate change, and many other important issues. How did this distrust of expertise emerge?

Shapiro: One of the most damaging results of the assaults on reason and science has been the declining legitimacy of expertise. Obviously, experts aren’t always right. We shouldn’t expect them to be. At least since John Stuart Mill, it’s been conventional for scientists always to think that the current state of knowledge is fallible and at least partly wrong. But the answer isn’t to embrace soothsayers or indulge people who claim to have their own truth. The answer lies in improving scientific knowledge by understanding the reasons for past failures and pursuing new research in search of better answers.

Max Weber famously said that a difference between a scientist and an artist is that an artist can aspire to paint a perfect painting that will stand for all time, whereas even the best scientists know that their work is going to be superseded by future generations. If you can’t live with that, he said, you don’t belong in science. That’s spot on.

We must all recognize that we’re contributing to a work in progress that is in perpetual need of improvement. Engaging in that process is critical to enhancing our understanding. For example, we know more about the conditions for stable and effective democracy today than was known 50 years ago, and a great deal more than was known when the founders wrote the Federalist Papers. That progress came through reasoned analysis in the light of evolving experience and research. That knowledge is important.