Janine di Giovanni was reporting from Iraq in the months before the U.S. invasion in 2003 when she traveled to the northern city of Mosul. There, she discovered an ancient community of Christians who prayed in Aramaic, the language of Jesus.

The people she met were frightened by the prospect of the coming war, but also committed to staying in their homeland despite the hardships to come.

“I was so touched by their resilience and how they had clung to their faith and their land for 2,000 years despite periods of repression,” di Giovanni said.

Over her 35 years as a war correspondent, including several years as senior foreign correspondent for the Times of London, di Giovanni has covered disastrous conflicts in Africa, the Balkans, and the Middle East. She has seen how faith can guide people, herself included, through violence and chaos.

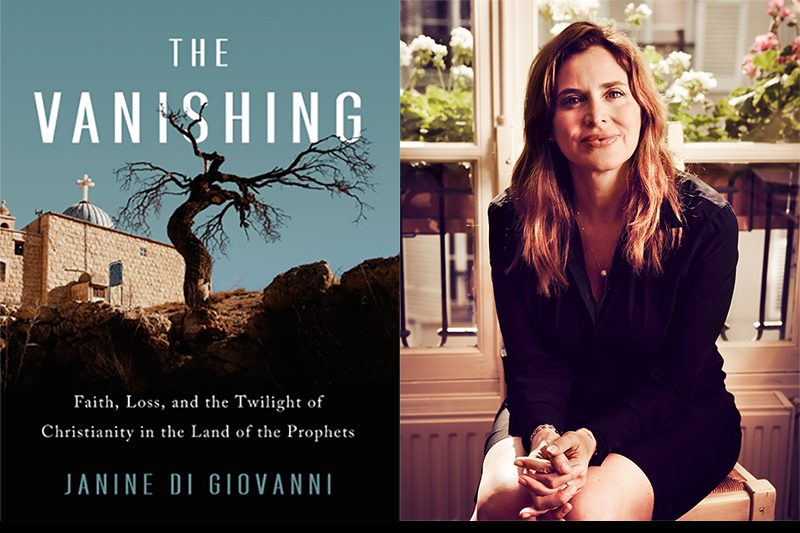

Her latest book, “The Vanishing: Faith, Loss, and the Twilight of Christianity in the Land of the Prophets” (PublicAffairs), examines the plight and potential disappearance of Christian communities across Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and Palestine. She documents the experiences of individuals determined to practice their faith and preserve their ancient traditions while constantly under threat.

Di Giovanni, a senior fellow at Yale’s Jackson Institute for Global Affairs, recently spoke to YaleNews about the dangers faced by Christian communities in the Middle East, the meaning of faith, and how her own faith has sustained her during difficult times. The interview has been edited and condensed.

What sort of peril are the Christian communities you write about encountering?

Many Christians in the region have encountered violent extremist groups that want to exterminate them. In Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State wanted to wipe Christians off the face of the Earth. They subjugated them and forced them to convert to Islam or be killed. They enslaved women. They burnt their farms and villages. They reduced their churches to rubble.

In Egypt, laws prevent Coptic Orthodox Christians from building churches. It’s not like in the United States where a decline in Christianity is simply a matter of young people not going to church. It’s a direct and often violent assault on an ancient people who have inhabited that land for 2,000 years. They’re like the martyrs in the Roman times.

Climate change also is a factor. According to the United Nations, Iraq is facing rising temperatures, declining rainfall, and more frequent sandstorms. Most of the Christians there are farmers, so their livelihoods are under threat from the changing climate. They’re leaving as a result. This is true across the Middle East. If current trends continue, there will be no Christians in the region within 100 years.

You interviewed hundreds of people from Christian communities across the Middle East. Do any stories or experiences stand out to you?

There are so many. There was a young man in Cairo who belongs to a Christian Copt community in which people make their living picking garbage. He told me how while growing up, he always felt like “the other.”

I also think of the Christians in Gaza who are caught between the Israeli siege and the rule of Hamas. Due to the severe travel restrictions placed on Palestinians, they can’t leave Gaza to visit Bethlehem at Christmas.

And I think of an ancient monastery in Iraq that I visited one evening. It was about six o’clock, maybe later, and the sun was setting. I heard this ethereal singing. I entered the monastery and found a room where a Chaldean monk was chanting in Aramaic. It was the evensong, which is the evening prayer. He sat with me and spoke to me about faith and about being rooted to this land and how vital it was that Christian people remain there. I recall the Christians who told me about how they fled ISIS, taking nothing and leaving their homes in the middle of the night. I have many, many striking memories of the people I met.

What would be lost if Christian communities were to entirely disappear from Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and Gaza — the places you cover in the book?

They will lose a crucial part of their cultural and social mosaic. Christians are important minorities groups in these places — ones with roots tracing back 2,000 years. The Jewish community has disappeared in Iraq, leaving a deep hole in the country’s social fabric. The people I wrote about are facing the same bleak future, but they form a rich part of their countries’ cultural heritage. One Iraqi politician told me that an Iraq without the Christians is no longer Iraq.

In the book, you reflect on the meaning of faith. What can non-believers draw from those reflections?

The book is about faith, not religion, and I wrote it for believers and non-believers. I think it will appeal to anyone searching for meaning in these difficult times. I have many friends who don’t believe in God or aren’t religious, but during the pandemic, they desperately wanted to believe in something. The world was spiraling into uncertainty.

I remember many years ago I had a dear friend who was a Serb and she was Orthodox, and I went to Mass with her. I’d never been to an Eastern Orthodox service.

“Why is there a curtain before the altar?” I asked.

“Because you’re not meant to see God, you’re meant to feel him,” she said.

Building on that idea, I think some people feel God in nature. Some people feel God in everyday miracles that they might encounter. Some might feel God in the kindness of strangers. This isn’t a book about judging people’s beliefs. Rather, it’s about where human beings turn for comfort and strength in times of great crisis.

What does your religious faith mean to you?

I’ve been a war reporter for 35 years. My father once reminded me that there are no atheists in foxholes. You discover this is true if you’ve ever faced extreme danger. I’ve had guns pointed at my head. I’ve been caught in bombing raids that killed people around me. There were moments that I thought might be my last on Earth in which I prayed for protection.

I’m not a good Catholic like my parents were. They didn’t eat meat on Fridays and attended the long masses on Good Friday, and things like that. I don’t, I’m ashamed to say. All the same, faith in God sustains and enriches me. It is the moral compass by which I live my life.

The Jackson Institute is in the process of transitioning into the Yale Jackson School of Global Affairs. You’ve been a senior fellow at Jackson since 2018. How do you enjoy teaching there?

I absolutely love it. I’m teaching a graduate-level course this semester called “Four Conflicts through a Human Rights Lens,” and my students are just extraordinary. They inspire me. Every year, I learn as much from them as they learn from me.

Jackson is an amazing hybrid of experienced practitioners and top-flight academics working together to train the next generation of leaders. That’s a heady thing. I’ve been in the field as a journalist covering and studying war, conflict, and post-conflict reconstruction for 35 years. There will come a time when I can’t travel to war zones. I’m very happy to have the opportunity to help train a new generation to do that vital work.