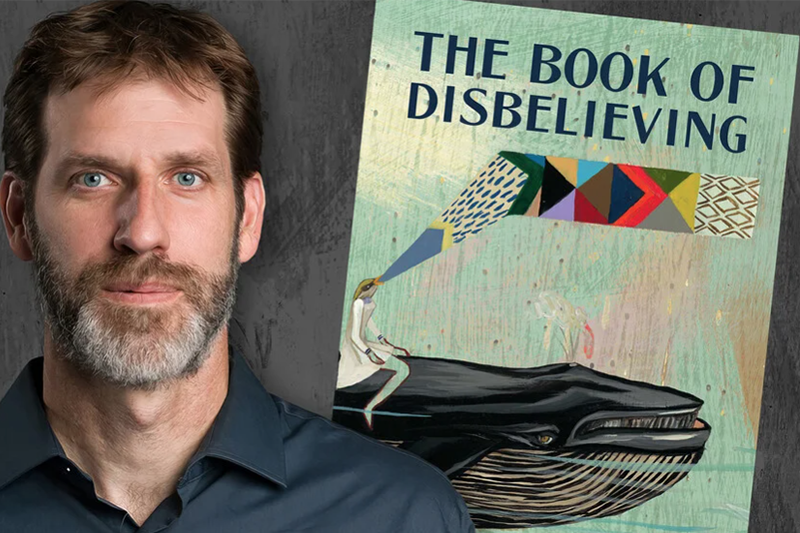

David Lawrence Morse, who teaches writing at the Jackson School, discusses his new collection of short stories.

In his day job as a lecturer and director of the writing program at the Yale Jackson School of Global Affairs, David Lawrence Morse teaches students to craft compelling narratives that can influence public policy.

But Morse is also an accomplished fiction writer. His first collection of short stories, “The Book of Disbelieving,” (Sarabande Books), is available now. The book’s nine stories explore existential questions within complex worlds, tempering dark subject matter with humor and absurdity. His characters’ challenges are grounded in reality, evoking existential crises.

Morse, who teaches classes on policy writing, persuasive writing, and policy-focused journalism at the Jackson School, recently spoke to Yale News about the process of writing short stories, the questions he explores in his fiction, and how the craft of narrative writing can help students pursuing careers in diplomacy and international relations. The interview has been edited and condensed.

In many of these stories your characters accept a dominant set of social beliefs that govern their behavior but are challenged in some way. What do you hope readers take away from watching your characters struggle with doubt or disbelief?

David Lawrence Morse: We live in a time where our society is driven by epistemological conflict. We are finding ourselves divided into different social or political or ideological groups, unable to agree on the facts or the nature of reality itself. So that’s deeply troubling.

Thinking about that caused me to dwell on how our understanding of reality is predicated, to an unsettling degree, on the beliefs and customs of our community, which in turn got me thinking about how challenging and difficult it is to think independently and challenge the prevailing wisdom of those around us. About how hard it is to develop a coherent and consistent understanding of reality, and to what extent we even want to do that, to what extent we even want to challenge or to develop a coherent and consistent understanding of reality. It’s been shown that people who are clinically or chronically depressed have a more accurate understanding of themselves than others. So, in other words, admitting the true nature of reality is difficult and destabilizing and maybe not even completely desirable.

We all have to tell ourselves stories, comforting stories, to get through life. I want readers to ask themselves, “What comforting stories, or what fables, or what myths do I tell myself or do I myself believe? And of those stories that I tell myself, how much of that is a fantasy? How much of that is harmless? And how much of that is essential?”

In one of the stories — “The Great Fish,” about a colony living on a large fish/whale — the narrator struggles to accept the possibility of his home fish dying. The idea of a dying world is certainly a relevant topic — was that an intentional parallel to our modern day?

Morse: I’d say yes and no. One thing I learned fairly early on writing fiction was that my tendency is to think analytically, and that doesn’t necessarily behoove a fiction writer. In my early attempts at writing stories, I would start with an argument or a philosophical principle and then would try to write a story that illustrated that argument or idea, and those stories ended up being pretty clunky and didactic, and not very interesting. I had to learn to restrain that impulse to think analytically — to try not to think very much, as I was telling a story, about what it might mean, but to just allow myself to explore the characters and circumstances in the narrative itself and see where that might lead.

At some point in writing this story, or maybe by the end of it, I started to think exactly in the terms that you’re suggesting, that this fish really is a metaphor for the planet that we live on, this planet that’s moving through the universe as the fish is moving through the sea, and this narrator regards himself as a caretaker of that fish, as we are caretakers of the planet. I did think about that, but I tried not to be too heavy-handed about asserting that analogy.

How can learning about crafting narratives assist students at the Jackson School of Global Affairs as they pursue careers in diplomacy and international relations?

Morse: We’re all busy crafting narratives to help explain who we are and what we do, either as individuals or collective entities. In my upcoming class, “Narrative Storytelling and Policymaking,” I will help policy students better understand the ways that narratives influence politics and policy, and how to shape narratives to influence politics and policy. I’ll argue that it’s not only facts that influence policy and politics, it’s the stories that are told about the facts. Politicians, corporations, and NGOs do this. So, you could argue that politics is a rhetorical battle between competing narratives. The class will help students better understand the way storytelling works in the political space and help them better understand how they themselves can craft available facts into a story that compels an audience to better understand an issue, or even to agree with them.

That being said, in that class and in my teaching at the Jackson School in general, I argue that there are some ethical questions raised by narrative storytelling. Our lives don’t work out the way stories do. My life might have a beginning, middle, and end the way a story does. But a typical story also needs a conflict, rising action, a crisis, and a resolution, which my life probably won’t have. So, if I want to tell the story of my life in a way that is dramatically compelling, I’d have to impose a narrative structure on it. That’s artificial. So anytime we’re telling a story about the raw facts of existence, we’re imposing an artificial structure on it. And when we do that, we’re shaping reality with an agenda, and we may be inclined to leave out facts that are inconvenient.

We may just choose to focus on some aspects of the story and not others, but when we do that, we are shaping other people’s understanding of reality and trying to get them to arrive at a certain meaning or conclusion. I don’t want my students to craft narratives that distort reality in a way that deprives readers of an understanding of what’s actually happening.

With these fantastical fables grounded in worldly subjects, what do you hope readers walk away with?

Morse: Some of these stories are quite dark, but in most of the stories, there’s an element of humor and comedy alongside of or growing out of the darkness. I’ve been focusing so much on these larger philosophical themes, but I also want readers to be amused. There’s a quote that I like, by a writer named P.J. Kavanagh. He says that “humor is the most serious response to our absurd fates,” and I like that.

I do think our lives are fairly absurd. You could respond to that with despair, as we all do sometimes. But I also think it’s healthy and therapeutic to be able to laugh as well. That’s partly the point of the stories, in addition to some of the other arguments I’ve been making. I hope readers will be able to see that life is dark and absurd, but if we can adopt a certain perspective and see our lives with humor, it’s easier to get through it.

And even though the book is called “The Book of Disbelieving,” there’s a whole range in the book of responses to the question of belief. It’s not a treatise against believing, it’s an exploration of the nature of belief, and even the need for belief. We all need to believe in something.