As former lead climate lawyer for the U.S. State Department, Susan Biniaz spent more than 25 years negotiating at global climate talks. This semester, she taught students how it’s done.

Let’s say it’s 2005. Representatives from 12 countries are gathered to craft a negotiating mandate for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. In just under two hours, the parties must agree to the procedural and substantive rules for brokering a global climate agreement. In the process, they must reach consensus without forfeiting their national priorities.

That was the challenge presented to students on a recent afternoon during a meeting of the class “Negotiating International Agreements: The Case of Climate Change” (Global Affairs 570). Twenty-three students gathered in Harkness Hall for their first mock negotiation, assuming the roles of international representatives hammering out a mandate.

The class offered a realistic microcosm of what happens when countries convene for thorny negotiations, as they are this week in Glasgow, Scotland, for the UN Conference of the Parties (COP) 26, said Susan Biniaz ’80, a Jackson Institute Senior Fellow who has taught the course each fall since 2018.

She would know. As former lead climate lawyer for the U.S. State Department, Biniaz, who also has an appointment Yale School of the Environment and has taught at Yale Law School, spent more than 25 years at the negotiating table during international climate talks, including the historic Paris summit in 2015.

“Sue has a staggering depth of experience in this field,” observed David Foster ’23, a Jackson Institute Global Health Scholar who represented Singapore during the classroom exercise.

Biniaz will be at COP 26 in her current role as a climate and foreign policy deputy for Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry ’66, who founded the Jackson Institute’s Kerry Initiative, an interdisciplinary program that tackles pressing global challenges.

Also at COP 26 will be Victoria Gramuglia, a M.E.M. candidate in the Yale School of the Environment, who acted as a delegate for the Marshall Islands in Biniaz’s class. She’ll be there with a cohort of more than 20 students who are supporting non-governmental organizations and country delegations; in all, dozens of Yale faculty, staff, and students will take part in the conference.

Debate without stalemate

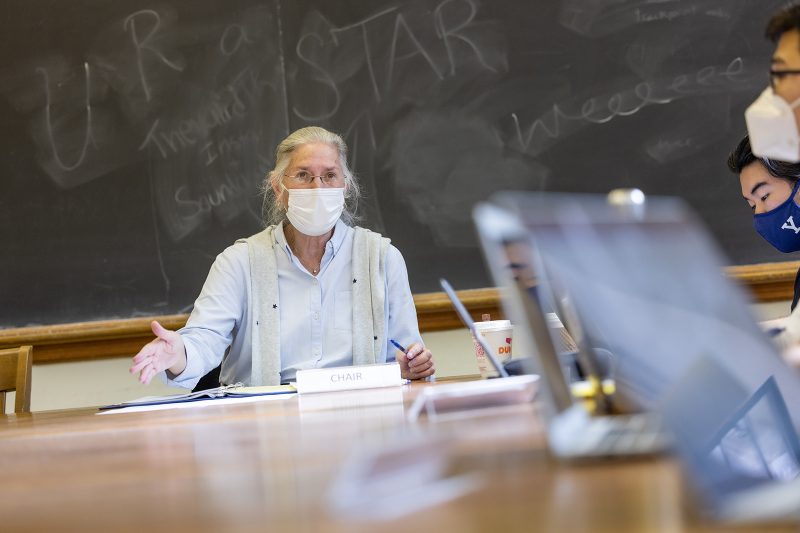

Biniaz wears her eminence lightly. Sitting at the head of the table, silver hair held in a bobby-pinned bun, a cardigan draped over her shoulders, she affably greeted the students as they trickled in. Once everyone was present, Biniaz, playing the role of chair, brought the room to order.

Biniaz wears her eminence lightly. Sitting at the head of the table, silver hair held in a bobby-pinned bun, a cardigan draped over her shoulders, she affably greeted the students as they trickled in. Once everyone was present, Biniaz, playing the role of chair, brought the room to order.

Nico Esguerra, an M.A. student at the Jackson Institute and course assistant, who served as secretariat, projected the draft text onto a screen and transcribed the delegates’ proposed amendments.

Almost immediately, disagreements emerged.

The U.S. team suggested lopping off a reference to “principles” in the first sentence. Amendments were added to amendments. Saudi Arabia proposed an additional paragraph introducing the concept of “common but differentiated responsibilities.” Ripples of dissent were heard from the U.S. and Japanese teams.

The discussion was five minutes old.

“We are getting further away from consensus rather than closer to it,” Biniaz observed. “Any problem-solving suggestions?”

When the stalemate persisted, Biniaz sent representatives from Japan, the U.S., Saudi Arabia, Russia, and Brazil into the hallway to keep haggling over the first paragraph while the rest of the class carried on through the document.

“That’s very real-life,” Biniaz told the class. “It’s a way of making the negotiation move along.”

Biniaz is no stranger to protracted arguments over recondite terms. In 2011, it was she who successfully ended that year’s climate summit in Durban, South Africa, which had dragged into overtime, by proposing that the phrase “legal outcome” be replaced with “agreed outcome with legal force,” according to Todd Stern, who was then the senior American climate change envoy.

“That was the last sticking point,” he told the New York Times at the time. “And then we were done.”

For the student teams, negotiations again stalled when they reached the third section of the preambulatory text:

“Emphasizing the urgency of addressing climate change, including deep cuts in global emissions.”

By then the teams’ positions — provided by Biniaz to provoke friction but also leave room for compromise — had snapped into focus. The United States resisted the notion that developed countries be held primarily accountable for runaway global emissions; China pushed back on developing countries shouldering responsibility for a problem they didn’t create; Saudi Arabia introduced doubt over whether climate change was a problem.

Before long, the section had morphed into tortured free verse:

“Emphasizing [the urgency of addressing] climate change [through adaptation efforts [as appropriate] and/, including/such as] deep cuts in global emissions [[led] by developed countries[/mature economies] [and other countries]/Annex 1 countries/high carbon-emitting countries/from all parties/including emerging countries/taking into consideration the concerns of developing countries in regards to the economic development and poverty elimination goals] [while noting the extraordinary situation for developing countries] [with emphasis on equity].”

Biniaz signaled that it was time to move on. Out into the hallway went the paragraph.

As the clock ticked, Biniaz prodded the students to use language that would promote consensus. “Try to make proposals that will get agreement from other countries,” she urged them. “We all know your negotiating positions now.”

The entreaty worked. Concessions came swiftly. And with minutes left, the class returned to the third paragraph of the preambulatory text, settling on a multi-claused compromise:

“Emphasizing the importance of addressing climate change, through adaptation efforts, and cuts in global emissions, from all Parties, with developed countries taking the lead and other Parties contributing.”

“It quickly became clear that climate negotiations are a bit like eight people playing tug-of-war with an octopus,” said Martin Wolf, a postdoctoral associate at the Yale School of the Environment and member of the Saudi Arabia delegation. “No one quite gets what they want — especially the octopus!”